The networking test pyramid

An automated test suite is the key to continuous integration (CI), the DevOps practice of rapidly integrating changes into mainline. The test suite is run on every change to check that individual modules and the full system continue to behave as expected as developers add new features or modify existing ones. A high-quality test suite gives developers and reviewers the confidence that the changes are correct and do not cause collateral damage.

As networks become more like software (“Infrastructure-as-Code”), automated test suites—sometimes also called “policies” or “polices-as-code”—are essential to safely and rapidly evolving networks to meet new business needs. However, little guidance is available for network engineers toward creating a good test suite. What are all the types of tests that one should consider to cover all the bases? What is the purpose of each type and how do different types relate to each other?

To help create high-quality test suites, we present the networking test pyramid. This pyramid is adapted from the well-known software test pyramid and groups tests into increasing granularity levels from checking individual elements of the network to checking end-to-end behavior. While this concept applies to all types of network testing, our focus is on testing network configurations—and changes to them—because most outages are related to configuration changes. The tested configurations and changes may be generated manually or automatically (e.g., using templates and a source-of-truth).

In addition to a sound conceptual framework, creating a high-quality test suite also needs a practical testing framework. As anyone who has written automatic tests will testify, the choice of this framework is critical and directly influences what you can or cannot test. An ideal test framework enables you to easily express tests at multiple granularities and frees you from worrying about low level details such as syntax and semantics of various device vendors. We will show how Batfish, an advanced network configuration analysis framework, rises to this challenge.

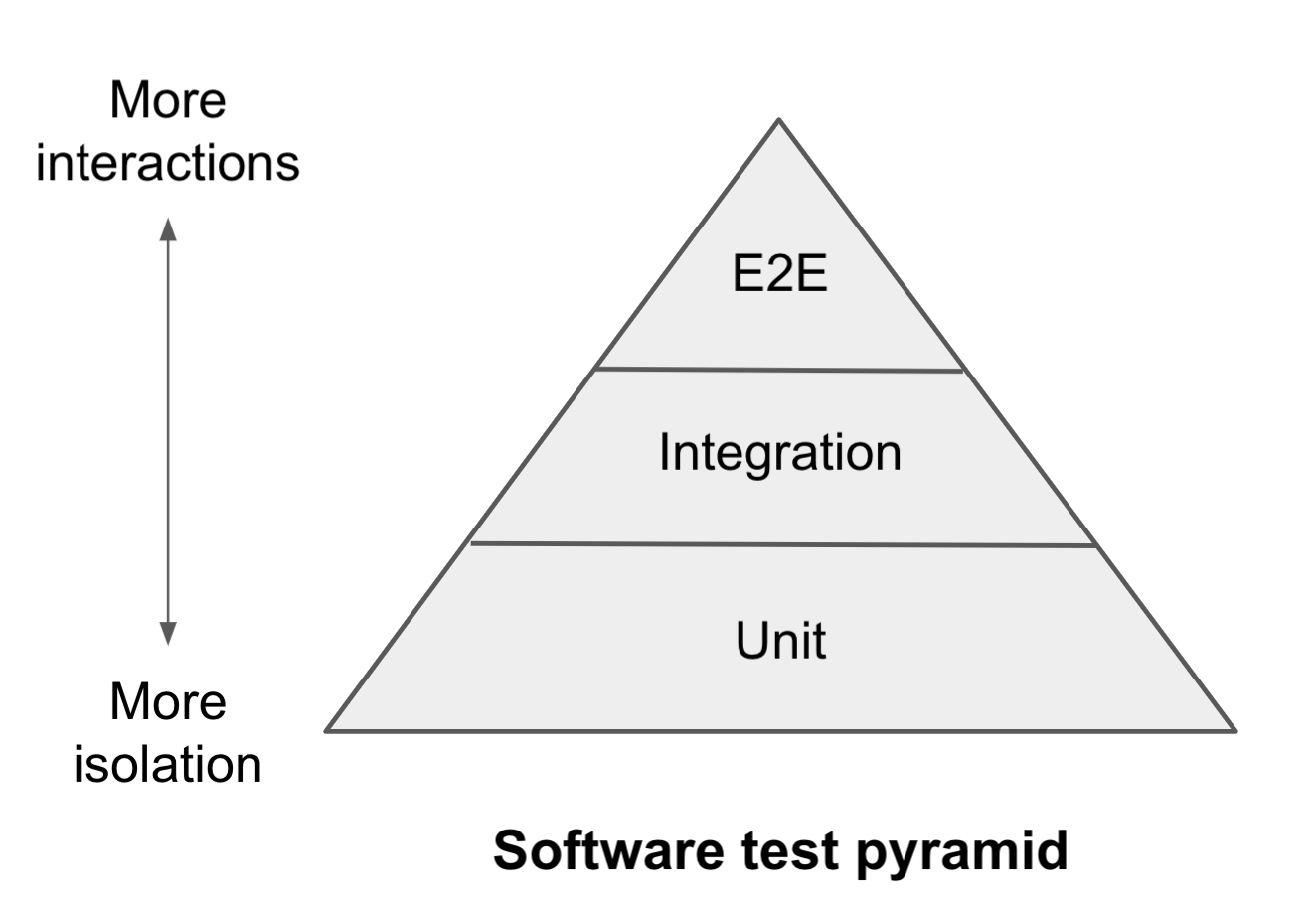

The Software Test Pyramid

Before discussing the networking test pyramid, let us review the software test pyramid. Mike Cohn introduced the software test pyramid in his book “Succeeding with Agile” in 2009. Several versions of the pyramid have been proposed since. We use Martin Fowler’s version as our reference.

At the bottom, we have unit tests that check individual modules; in the middle, we have integration tests that check interactions between two or more modules; and at the top, we have end-to-end tests that check end-to-end behaviors such as responses to user requests. As we move from bottom to top, the focus changes from testing isolated aspects of the system to testing complex interactions.

Because there are fewer interactions at the unit test level, these tests tend to be faster to execute and their failures easier to debug. Unit tests can also check modules for a broader range of inputs that may be hard to reproduce as part of an integration or E2E test. However, these advantages of unit tests do not imply that higher-level tests can be ignored. They are closer to what users and applications experience and validate interactions that may have been left untested by unit tests because of a missing test case, the difficulty of testing, or incorrect assumptions about how other modules behave. There have been many an Internet meme that drive home this point.

Given the unique strengths of different pyramid levels, a good test suite contains tests at all levels. That helps you find and fix errors easily, achieve better test coverage, and directly validate user experience. By borrowing the test pyramid concept, we can develop networking test suites with similar advantages.

The Test Pyramid applied to Networking

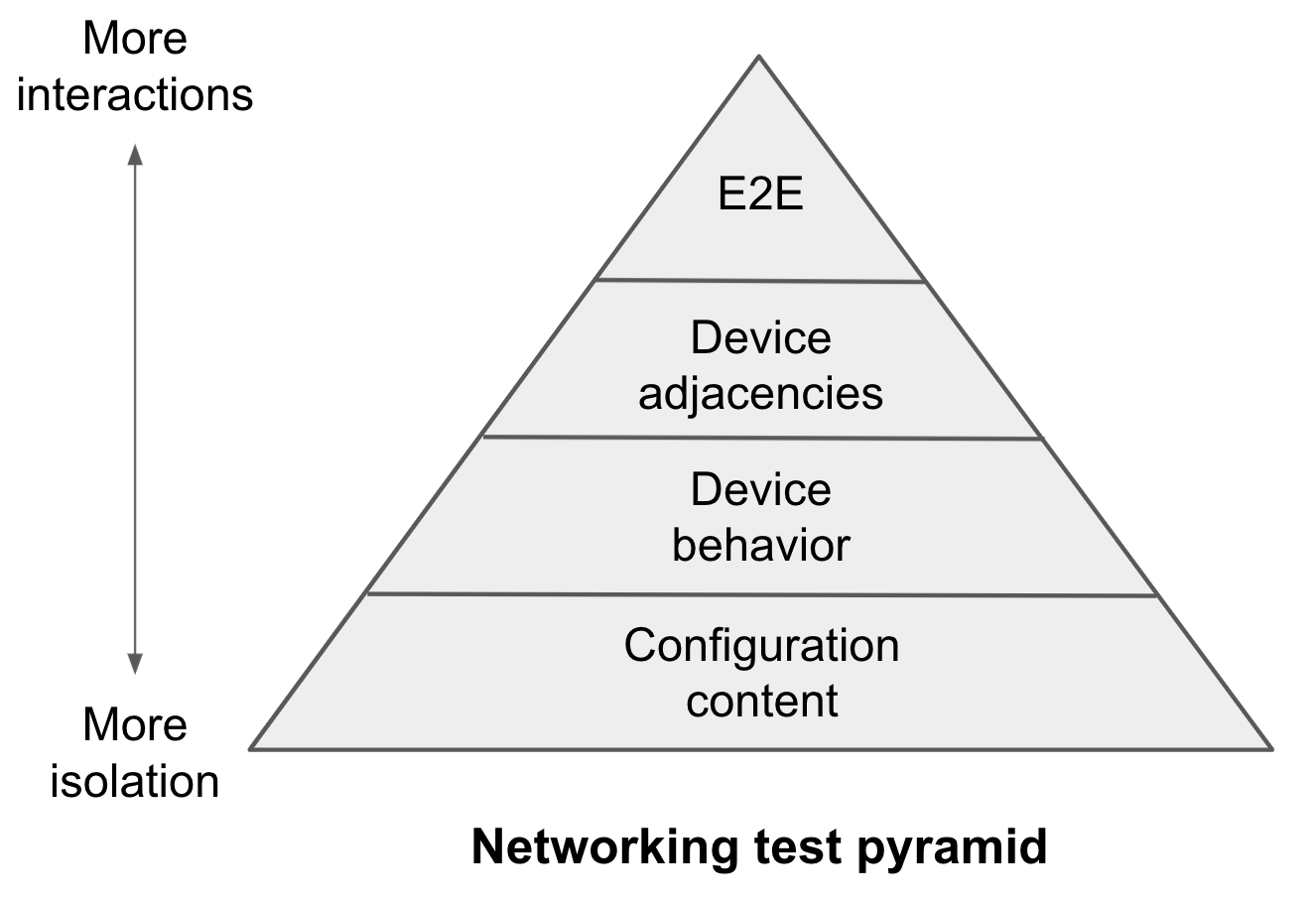

Our adaptation of the test pyramid is shown below.

While it has a different number of levels and uses different terminology, it retains the essence of its software test pyramid. As we move from bottom to top, the focus changes from testing localized, isolated aspects to complex interactions. Listing the levels from bottom to top:

- Configuration content: At this level, you test if device configurations contain what you expect. It includes checks such as whether interface IP addresses are correct, whether BGP peers are assigned to peer groups, whether access control list (ACL) names follow site standards, and whether certain lines appear in the config. You are not validating behavior at this level (which will happen later) but operating at the textual layer of configurations. You are primarily checking that human, coding, or source-of-truth error (depending on how you generate configs) has not led to improper configuration content.

- Device behavior: At this level, you test the behavior of individual devices such as which packets its ACLs (access control list) permit/deny and how its route maps process BGP announcements. When you tested configuration content, you did not directly test behaviors which result from the interaction of many configuration lines. For instance, the behavior of an ACL depends on the order of ACL lines and on definitions of address groups that it uses; ACL behavior testing ensures that all of these aspects combine to produce expected behavior. As the debate about unit-vs-integration tests illustrates, it is important to test higher-level behaviors even when lower-level aspects are tested well.

- Device adjacencies: At this level, you test if devices can establish the right adjacencies such as BGP sessions, GRE tunnels, and VPNs. These adjacencies form the foundation of network behavior, so testing them directly is important. It is possible to have a test suite where all configuration-content and device-behavior tests pass but protocol adjacency tests fail due to incompatibility between devices.

- End-to-end: At this level, you test the end-to-end behavior of the network control and data planes, whether it propagates and filters routing information as expected and whether it forwards and drops traffic as expected. These tests are powerful because they directly test applications experience and exercise a broad range of underlying aspects. When these tests pass, applications are more likely to experience a functioning network and give you confidence that many of the underlying aspects are correct and interacting as expected.

If you wanted to map these levels to the software pyramid, one could think of a device as a module. So, the device behavior, device adjacencies, and E2E networking levels map respectively, to unit, integration, and E2E software levels. The software counterpart of configuration content testing would be analyses such as linting and checking compliance with formatting and variable naming rules. These non-behavioral checks are not in the software test pyramid, though software does undergo these tests (often as part of the build process).

Putting the Networking Test Pyramid to Practice

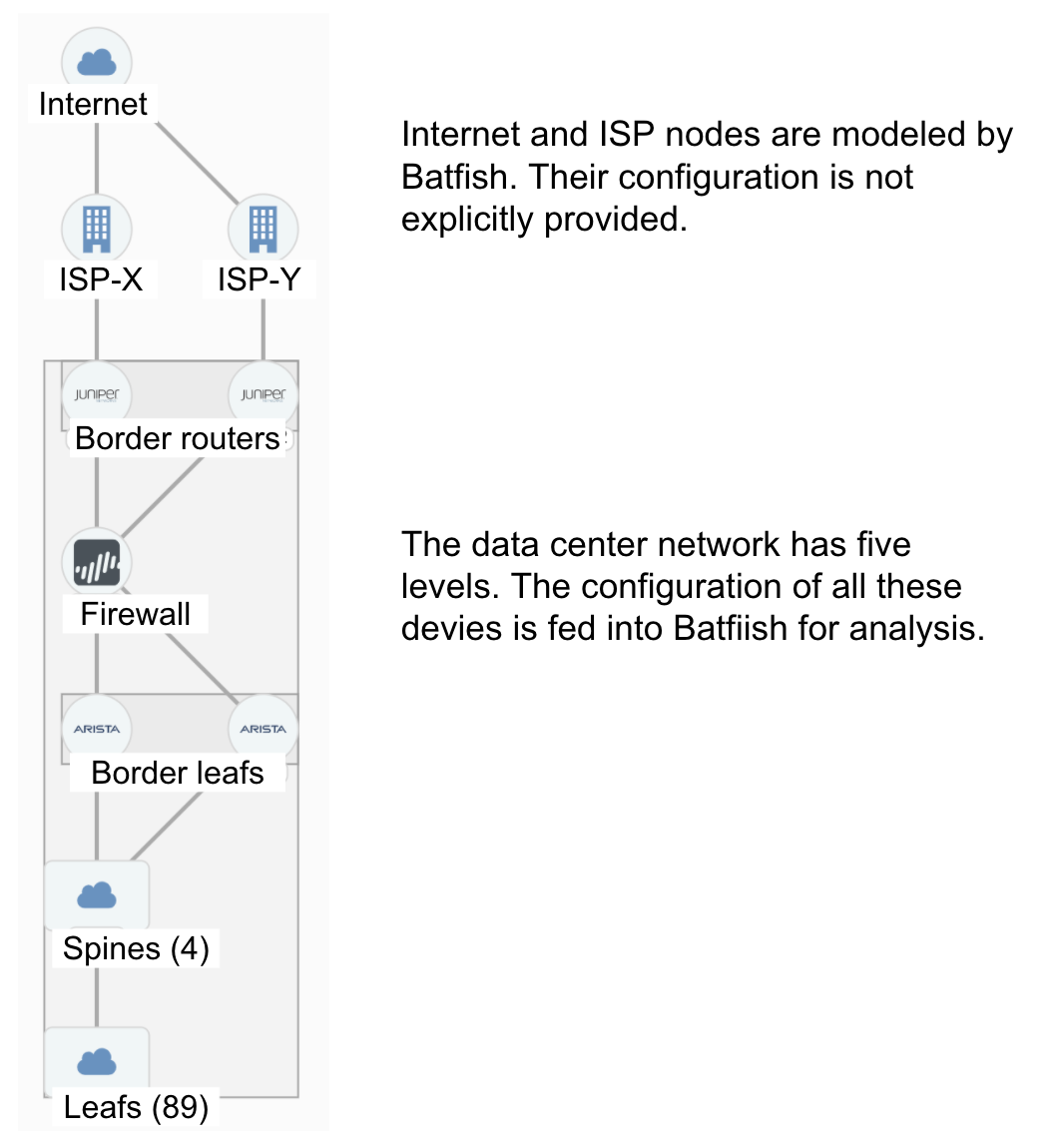

Now that we have learned the theory of the networking test pyramid, it is time to put it to practice. We do that by developing a test suite using pybatfish, the Python client of Batfish, for the data center network below. It is a multi-vendor network with an eBGP-based leaf-spine fabric (Arista), along with a firewall (Palo Alto), and border routers (Juniper MX) that connect to the outside world.

In this data center, there are many aspects you’d want to test to get confidence in its behavior and configuration changes. For brevity, we will focus on testing aspects related to connectivity between leafs and to the outside world. A comprehensive test suite will check many other aspects as well such as NTP servers, interface MTUs, connectivity to management devices, and so on. This GitHub repository has the code for all the tests below, implemented in the pytest framework.

Configuration content

We start with the lowest level of the pyramid, where we check configuration content. Given our focus on basic connectivity, we may write the following tests.

- All interfaces IPs must have expected values. The expected values depend on the setup. Exact value for each interface could come from an IPAM or the requirement could be simply that all values should be drawn from certain prefixes and be unique. Our example tests use the second criteria.

- All local ASNs must have expected values. Again, the expected values depend on the setup. Our example tests assume that each layer of the DC must use local ASNs within a range and their ASNs should be globally unique.

- All configured BGP peers must have expected remote ASNs. This test is based on the ASN allocation above, so the remote ASNs of spine-facing peers on leafs must be within the range used for the spines.

- All leaf routers must have EBGP multipath enabled, to load balance via ECMP.

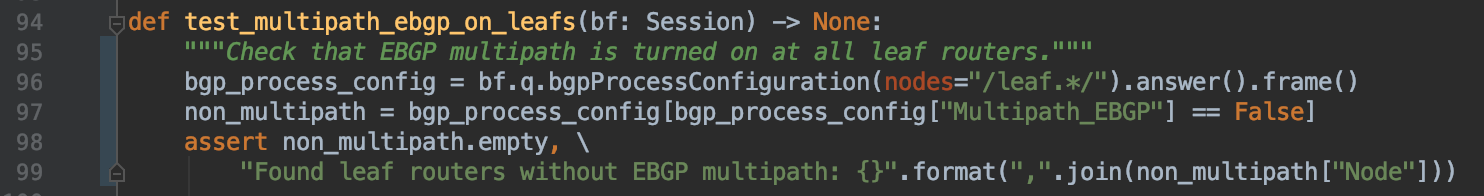

Pybatfish implementations of all these tests is here. The eBGP multipath test is:

Line 96 uses Batfish’s bgpProcessConfiguration question to extract information about all BGP processes on leaf nodes. This information is returned as a Pandas DataFrame—Pandas is a popular data analysis framework and a DataFrame is a tabular representation of the data—in which rows correspond to BGP processes and columns to different settings of the process. Line 97 extracts BGP processes for which Multipath_EBGP is False. Finally, Line 98 checks that no such processes were found.

We see that tests take only a few lines of Python, and nowhere did we need to account for vendor-specific syntax or defaults. This simplicity stems from the structured, vendor-neutral data model that Batfish builds from device configs.

Device behavior

Having tested important configuration content, you can now test that various elements of the configuration combine to produce intended device-level behaviors. You may write the following tests.

- The access control list (ACLs) at the border router must block incoming traffic from private address spaces and the set of malicious sources that we have identified.

- The route map at the border router must filter routing announcements for private address spaces.

- The route map at the border leafs must aggregate SVI prefixes before propagating them upwards in the data center.

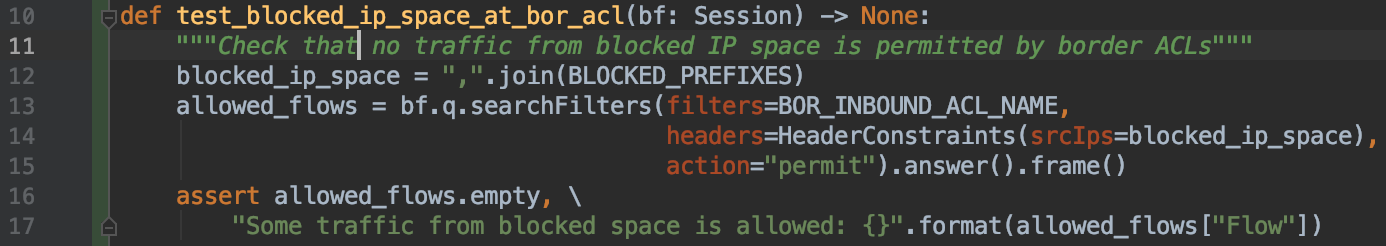

Pybatfish implementation of these tests is here. The ACL test is:

Line 13 uses the searchFilters question of Batfish to find any traffic from the blocked IP space that is permitted by the ACL, and then Line 16 asserts that no such traffic is found. In contrast to the alternative of grep’ing for blocked prefixes in the device configuration, this test actually validates behavior. Grep-based validation is fragile because a line that permits some or all of the blocked traffic may also appear in the configuration, resulting in you falsely concluding that the traffic is blocked.

Device adjacencies

Now that we have validated the behavior of individual devices, we can validate different types of adjacencies between devices using these tests:

- All pairs of interfaces that we expect to be connected (based on LLDP data or a source of truth like Netbox) must be in the same subnet.

- All (and only) expected BGP adjacencies must be present.

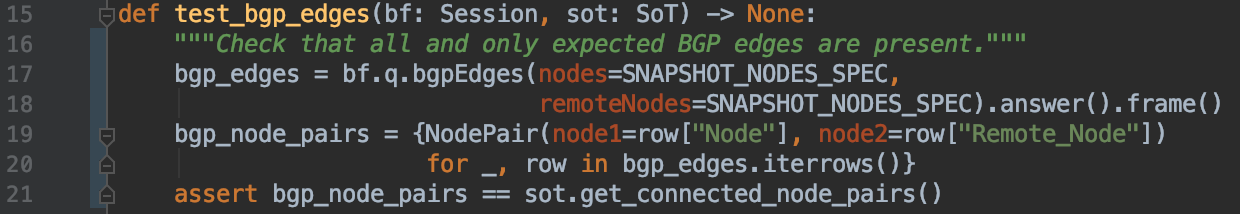

Pybatfish implementation for both tests is here. The second test is:

This code is using the bgpEdges question of Batfish to extract all established BGP edges in the network. BGP adjacencies that do not get established due to, say, incompatible peer configuration settings, will not be returned. The question returns an edge per DataFrame row, which Line 19 transforms into a set of all node pairs. Line 21 asserts that this set is identical to what we expect based on the source of truth.

End-to-end

With the lower-level tests in place, you are ready to test important end-to-end aspects of the network’s control and data planes. You may write the following tests:

- The default route must be present on all routers. This route comes into the data center from outside. We want to test that it is propagated everywhere. Traffic to the Internet will be dropped if the default route is accidentally filtered somewhere.

- Each leaf router must have the route to all SVI prefixes. Because end hosts are in these prefixes, this test checks that routing within the data center is working well and all pairs of hosts have a path to each other.

- All public services hosted in the data center must be reachable from the Internet. No valid connection request should be dropped by the network.

- No private service must be reachable from the Internet. This security property must hold no matter how an adversary crafts their packet.

- Key external services, such as Google DNS and AWS, must be accessible from all leaf routers.

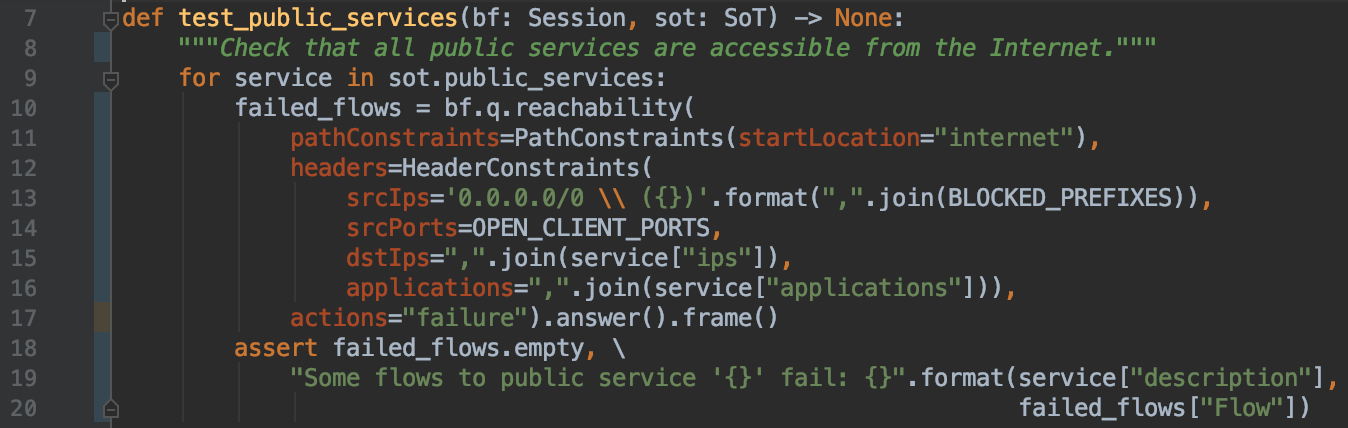

Pybatfish implementations of all these tests is here. The public services test is:

For each public service, it is using the reachability question of Batfish to find valid flows that will fail. Valid flows are defined as those starting at the Internet (Line 11), have a source IP that is not among blocked prefixes (Line 13), have a source port among ports that are not blocked anywhere in the network (Line 14), and have destination IP and port corresponding to the service (Lines 15, 16). It is then asserting that no valid flow fails.

This Batfish test is exhaustive. It is considering billions of possibilities in the space of valid flows, and it will find and report if there is any flow that cannot go all the way from the Internet to the service. Such strong guarantees are not possible if you were to test reachability of public services via traceroute.

Wrap up

That wraps up our example test suite. Hopefully, you could see how the pyramid helps you think comprehensively about network tests and how Batfish helps you implement those tests. After you’ve defined a test suite for your network, you’d be able to run it for every planned change. Imagine how rapidly and confidently you’d then be able to change the network. That is the power of a good automated test suite!

Check out these related resources

- Read “A practical approach to building a network CI/CD pipeline” to learn how to embed your test suite in an automation pipeline.